Part I: Understanding Progression in MS

Background Information

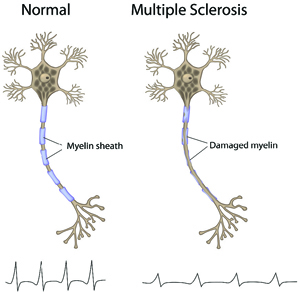

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a disease of the central nervous system (CNS). The CNS consists of the brain, optic nerves, and spinal cord. With MS, areas of the CNS become inflamed, damaging the protective covering (myelin) that surrounds and insulates the nerves (axons). In addition to the myelin, over time, the axons and nerve cells (neurons) within the CNS may also become damaged. This damage is referred to as neurodegeneration.

The damage to the protective covering and also to the nerves disrupts the smooth flow of nerve impulses. As a result, messages from the brain and spinal cord going to other parts of the body may be delayed and have trouble reaching their destination – causing the symptoms of MS. Described later in this booklet, these symptoms can include a wide variety of physical, emotional, and cognitive changes.

Areas of inflammation and damage are known as lesions, which are viewed on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. The changes in size, number, and location of these lesions may determine the type and severity of symptoms. While individuals with relapsing forms of MS are believed to experience more inflammation than those with progressive forms of MS, lesions still occur for individuals with all forms of MS. However, the lesions in progressive forms of MS may be less active and expand more slowly.

Shown above is an illustration of two nerve cells. The normal one on the left has a healthy nerve fiber, or axon, protected by myelin (insulation covering the nerve), and is able to transmit signals at a very fast speed – similar to electricity traveling along an electrical cord. The MS nerve cell on the right shows damage to the myelin, and as a result, signals do not travel well along the nerve.

Types of MS

MS affects each person differently. For many years, the most common types of MS had been classified as:

- relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS)

- primary-progressive MS (PPMS)

- secondary-progressive MS (SPMS)

- progressive-relapsing MS (PRMS)

However, these classifications are changing, and some experts are now grouping relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) and secondary-progressive MS (SPMS) together, as a continuum of the same disease. These are now frequently referred to as “relapsing forms of MS.” Additionally, progressive-relapsing MS (PRMS) and primary-progressive MS (PPMS) have also been grouped together. These are now frequently referred to as “progressive forms of MS.”

Initially, most people with MS experience symptom flare-ups, which are also known as relapses, exacerbations, or attacks. When someone experiences a relapse, he or she may be having new symptoms or an increase in existing symptoms. These usually persist for a short period of time, from a few days to a few months. Afterward, the symptoms greatly improve or remit completely, and these individuals may remain symptom-free for periods of months or years. This type of MS is known as relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS). Approximately 80 to 85 percent of MS patients are initially diagnosed with this form of the disease.

Over time, RRMS may advance to secondary-progressive MS (SPMS). This form of MS does not have the dramatic variations in symptoms that RRMS does, but rather has a slow, steady progression – with or without relapses. If relapses do occur, they usually do not fully remit.

Without treatment, approximately half of individuals with RRMS convert to SPMS within 10 years. However, with the introduction of long-term disease-modifying therapies (DMTs), fewer individuals advance to this latter form of the disease. Since 1993, and as of mid-2017, a total of 15 DMTs have been approved by the FDA and are available through prescription. All of these approved medications are aimed at slowing disease activity and delaying progression in MS.

Individuals who are not initially diagnosed with RRMS may be experiencing a more steady progression of the disease from the onset. Approximately 10 percent of the MS population is diagnosed with primary-progressive MS (PPMS), where individuals experience a steady worsening of symptoms from the start, and do not have periodic relapses and remissions.

Approximately 5 percent of patients are initially diagnosed with progressive-relapsing MS (PRMS). This type of MS steadily worsens from the onset, but symptom flare-ups – with or without remissions – are also present.

The Pathogenesis of MS Progression

All forms of MS share an underlying pathogenesis, which refers to the origin of a disease and its development. The pathogenesis of MS includes:

- inflammation – this is an autoimmune attack where an individual’s own white blood cells cause damage to his or her own neurons within the brain and spinal cord

- demyelination – this is damage to the myelin covering around nerves, caused by inflammation

- axonal degeneration – this is the shrinking, atrophy, and death of neurons

- remyelination – this is the body’s own attempt to repair damaged myelin, although this repair is often incomplete

- glial scar formation – this results in multiple scars within the brain and spinal cord at sites of damage from MS

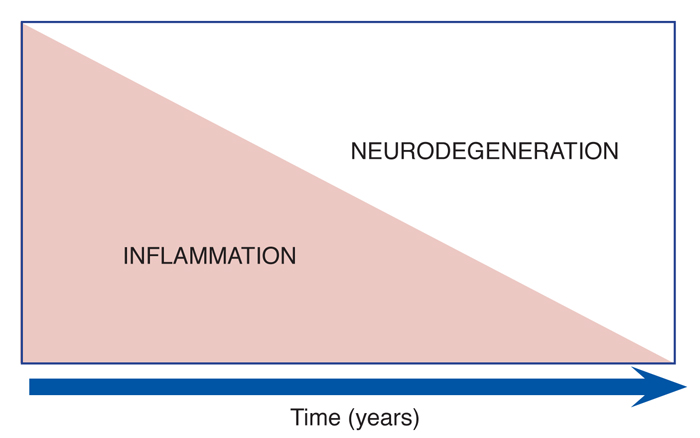

Research has shown that individuals with progressive forms of MS have predominantly neurodegeneration and less inflammation. This is in comparison to relapsing-remitting MS, where inflammation is the predominant driver of the disease with less neurodegeneration occurring early in the disease process.

Multiple Sclerosis Pathophysiology

Particularly with relapsing forms of MS, inflammation is greatly involved with the initial disease process. This causes damage to the myelin – the protective covering of the nerves in the central nervous system – and eventually damage to the nerves as well. As time progresses and fewer relapses are experienced, the disease involves increasingly less inflammation and more neurodegeneration, which is the breakdown or cell death of nerve cells.

The Measures and Assessment of Progression

► Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has revolutionized the ability to efficiently diagnose MS, track new inflammatory-disease activity – through the discovery of new T2 bright spots and/or new gadolinium-enhancing lesions (these are areas of disease activity with inflammation) – as well as monitor an individual’s response to MS disease-modifying therapies. Currently, an MRI scan provides the best biomarker for evidence of MS progression. MRI measures that most closely correlate to progression include:

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has revolutionized the ability to efficiently diagnose MS, track new inflammatory-disease activity – through the discovery of new T2 bright spots and/or new gadolinium-enhancing lesions (these are areas of disease activity with inflammation) – as well as monitor an individual’s response to MS disease-modifying therapies. Currently, an MRI scan provides the best biomarker for evidence of MS progression. MRI measures that most closely correlate to progression include:

- accelerated brain atrophy, which refers to faster brain shrinkage

- development of T1 hypointensities, also referred to as “black holes,” which indicate more neurodegeneration versus inflammation

Readers should note that many of the current MS therapies have been shown to decrease the accumulation of bright spots and black holes as viewed on an MRI, along with slowing atrophy rates. MS specialists encourage people with MS to review their MRI scans with their providers and to ask about these two types of disease measures.

Important note: MSAA may be able to help cover MRI costs through its MRI Access Fund program (certain income limits apply). To learn more, please visit mymsaa.org/mri or call (800) 532-7667, extension 120.

► The EDSS and Neurologic Exam

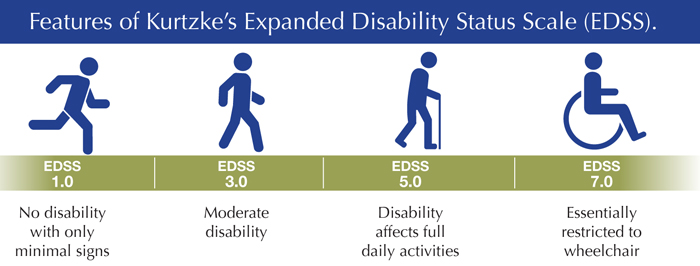

Kurtzke’s Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) is the oldest and most widely accepted measure of MS disability. The EDSS ranges from 0 to 10 in half-point increments, where 0 is a normal examination, 3.0 is moderate disability, 6.0 is where the person needs assistance to walk, and higher numbers refer to greater disability, largely in terms of mobility.

A trained MS clinician assigns a functional score to a patient in eight neurologic systems: pyramidal (referring to the motor system, with weakness and spasticity), cerebellar, brainstem, sensory, bladder and bowel, vision, cerebral, and “other.” These are all based on a standard neurologic examination. The EDSS is frequently criticized for being insensitive to small changes, being heavily dependent on mobility, not capturing cognitive impairment, being subjective in some assessments (rating scores can vary), and for not capturing the full range of disabilities.

► The Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite

The Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite (MSFC) is another clinical tool that assesses MS disability. Unlike the EDSS that is based on a standard neurological examination, the MSFC assesses disability using three “functional” tests. It summarizes the scores of the following:

- a timed 25-foot walk evaluating ambulation

- the nine-hole peg test evaluating arm function

- the paced auditory serial addition test evaluating cognition

The goal of this system is to capture information on key functional measures affected by MS, specifically leg, arm, and cognitive function. The MSFC is often used in connection with the EDSS in MS clinical trials. Many aspects of the MSFC, such as the timed 25-foot walk, are routinely monitored in MS clinics as well.

The Natural Progression of MS

Approximately one in every 750 individuals in the United States has MS. The natural progression of MS has changed over time. Early studies showed that the median time from onset of PPMS to needing a device (such as a cane) to assist with walking was 10 years, while more contemporary studies show that this has increased to 15 years. Another study showed that 25 percent of people with PPMS still did not require a cane after more than 25 years. Although difficult, individuals with MS should not compare their disease course with those of others, as every individual is different.

Risk factors for disease progression have been identified, but their interplay is complex. Early onset of disease and female gender are favorable factors associated with a better prognosis in terms of one’s long-term course of MS. For instance, individuals who were young at the onset of their MS have been shown to take a longer amount of time before their MS progresses to the point of needing a device to assist with walking, which is a score of 6.0 on the EDSS.

Relapses can still occur in people with progressive MS. Individuals with secondaryprogressive MS can have an occasional relapse, which is a new neurologic symptom that lasts more than 24 hours, in the absence of fever or infection. This occasional relapse is superimposed on progressive disease, characterized by a gradual decline.

For example, an individual with SPMS may notice worsening balance and walking issues over several years, and then notice over the course of hours to days, they have developed blurry vision in one eye and pain with eye movements. He or she may then be diagnosed with an MS relapse of optic neuritis, in addition to having a gradual decline in neurologic function over the course of years. This is different from RRMS, as individuals with RRMS only experience neurologic worsening in the setting of a relapse.

Criteria for Diagnosis and Description Modifiers

The word “progressive” has historically carried a negative connotation among members of the MS community. However, when this term was first coined, the understanding of the pathophysiology of MS – which is how the disease progresses and its effects – was very limited. Neuro-diagnostics, which use advanced technology to diagnose, evaluate, and sometimes treat certain neurological conditions, were in their infancy, and the therapies that could slow progression were lacking. Fortunately, the MS world is changing.

Currently, no criteria have been defined to determine definitively when a person with MS has progressed from RRMS to SPMS. However, criteria are in place for a diagnosis of SPMS, which requires the onset of the disease with at least one clinical relapse (differentiating it from PPMS), followed by a gradual decline in neurologic function over the course of at least six to 12 months. This decline must be separate from the worsening that occurs during relapses.

The diagnosis of PPMS has distinct criteria based on 2010 McDonald criteria for the diagnosis of MS. To receive a diagnosis of PPMS, a person with MS must have one year or more of gradual decline in neurologic function, in addition to two or more of the following:

- abnormal lesions consistent with MS on MRI

- two or more lesions consistent with MS in the spinal cord

- cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis consistent with the diagnosis

Individuals with RRMS are usually diagnosed between the ages of 15 and 40. The average age of onset of SPMS and PPMS is in the fifth and sixth decades of life, when people are in their 40s or 50s. While RRMS often affects women two-to-three times more often than men, the gender ratio in PPMS is equal between males and females.

In both SPMS and PPMS, the rate of decline in neurologic function occurs at a similar rate. Individuals with PPMS generally have more spinal-cord lesions than those with SPMS. It is important to note that the diagnosis of the type of MS is based on clinical history, which is determined through doctor visits and evaluations. Progressive forms of MS cannot be diagnosed with an MRI or spinal-fluid analysis alone.

As part of the 2013 International MS Phenotype Group revised MS classification criteria, three important modifiers were added to the description of MS: activity, worsening, and progression. These modifiers help to more accurately reflect the current disease process in a specific individual with MS.

- Disease activity refers to a new clinical MS attack (relapse) or a new bright spot (showing inflammation) on the MRI.

- Disease worsening simply reflects that a specific person’s neurological examination has gotten worse compared to prior examinations, possibly related to an MS attack (relapse).

- Disease progression indicates worsening on an exam, independent from an attack (relapse).

In summary, people with progressive MS can and do have attacks (relapses), albeit infrequently, and develop new spots (or lesions) on MRI. Both relapses and new lesions are types of disease activity. Additionally, MS may be “clinically silent,” showing no increase in symptoms, yet continuing to show signs of disease activity within the CNS, as seen on MRI. Conversely, these same people can experience long periods of time without progression and without worsening. These variations in disease activity show how dynamic MS is, while affecting each individual differently.

Non-MS Causes of Clinical Worsening

Clinical worsening in MS, or the gradual decline in function, should not immediately be attributed to MS as the only cause. Individuals with MS can also acquire other medical problems that can mimic MS progression. These include:

Clinical worsening in MS, or the gradual decline in function, should not immediately be attributed to MS as the only cause. Individuals with MS can also acquire other medical problems that can mimic MS progression. These include:

- cervical stenosis – a narrowing of the spinal canal in the neck, which can put pressure on the spinal cord and cause a worsening of gait, sensation, strength, as well as a worsening of bowel and bladder control

- vitamin deficiencies, such as B12

- thyroid disease

- other conditions not related to MS

As a result, a thorough evaluation by a neurologist as well as a regular follow up with a primary-care physician are important. If alternative causes are ruled out, then a neurologist may confirm that progression is directly related to one’s MS.