Cover Story: Finding Purpose in Life

By Laura Bradford

By Laura Bradford

Reviewed by Barry A. Hendin, MD

Edited by Susan Courtney

What is My Purpose in Life?

That’s a question many of us have likely pondered at some point, especially when standing at one of life’s many crossroads. It is, after all, natural to question your direction, your goals, your hopes, and a desire to help others. But did you know that finding and embracing that purpose may actually play a part in your physical and mental health? Additionally, some data suggest that the risk of developing certain autoimmune diseases may possibly be reduced.

To see how and why, let’s take it back to the beginning and Viktor Frankl, the Viennese neurologist and psychiatrist credited with introducing Purpose in Life to medicine for the first time. A holocaust survivor, Frankl credited his ability to survive his time in concentration camps to what was, essentially, his purpose in life (PIL) – to bring attention to PIL’s place in the medical world.

He shared his thoughts on PIL and how it helped him to survive those dark years in his book, A Man’s Search for Meaning. In a nutshell, Frankl believed that we are instinctively wired to have a purpose in life, and that having one, and pursuing one, will keep us healthy. This purpose, he says, differs from person to person as everyone has his or her own individual mission.

Unfortunately, as often happens in a world where everything – ideas, studies, technology – is ever changing, Frankl’s push to get PIL the attention it deserved met with some resistance. After all, how can one truly define, measure, and study a person’s perception of purpose?

Well, James Crumbaugh and Leonard Maholick, two of PIL’s earliest researchers, sought to do just that in 1964 when they created a scale to evaluate PIL. Comprised of 20 statements, they would ask patients to rate from 1 (low) to 7 (high). The scale sought to explore Frankl’s belief in a person’s will to find meaning in one’s life.

The pair crafted their statements to look, specifically, at the three areas Frankl identified as key components – meaning in existence, freedom to create meaning in life, and the will to find meaning in future challenges. The final score of the scale determined whether a person’s PIL was high or low.

Frankl’s Key Dimensions

In the first of Frankl’s key dimensions (determining meaning in existence), participants were asked to rate their answers to the following statements on that 1-to-7 scale, with a “4” being considered neutral.

- I am usually: completely bored (1), to, exuberant/enthusiastic (7).

- In life I have: no goals or aims at all (1), to, very clear goals and aims (7).

- In achieving life goals, I have: made no progress whatsoever (1), to, progressed to complete fulfillment (7).

In the second of Frankl’s key dimensions (freedom to create meaning in daily life), statements included such items as:

- I regard my ability to find a meaning, purpose, or mission in life as: very great (7), to, practically none (1).

- My life is: in my hands and I am in control of it (7), to, out of my hands and controlled by external forces (1).

- Facing my daily tasks is: a source of pleasure and satisfaction (7), to, a painful and boring experience (1).

For the third of Frankl’s key dimensions (will to find meaning in future challenges), statements included such items as:

- Life to me seems: always exciting (7), to, completely routine (1).

- Every day is: constantly new and different (7), to, exactly the same (1).

- After retiring, I would: do some of the exciting things I have always wanted to do (7), to, loaf completely the rest of my life (1).

Once all 20 statements were rated by a participant, the final score was tallied. The higher the score, the higher a person’s PIL, and, thus, the heightened motivational force for survival Frankl had described.

Despite Crumbaugh and Maholick’s efforts to quiet the skepticism surrounding PIL and its place in a person’s overall health with their scale, though, the subject faded into the background.

Until about a Decade Ago

Now, thanks to a preponderance of data, talk of PIL in relation to health is not only back, but it’s getting noticed for all the right reasons, according to Adam Kaplin, MD, PhD, former chief psychiatric consultant to the Johns Hopkins Multiple Sclerosis and Transverse Myelitis Centers, and clinician-researcher in the departments of psychiatry and neurology at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland.

Now, thanks to a preponderance of data, talk of PIL in relation to health is not only back, but it’s getting noticed for all the right reasons, according to Adam Kaplin, MD, PhD, former chief psychiatric consultant to the Johns Hopkins Multiple Sclerosis and Transverse Myelitis Centers, and clinician-researcher in the departments of psychiatry and neurology at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland.

“The data is showing us that one’s purpose needs to be in helping others,” Kaplin explains. “Just wanting more money or other hedonistic pursuits aren’t enough. Helping others is intrinsically rewarding in and of itself in a way that is very different than buying a car or a house.”

So What is Purpose in Life, Exactly? And How Does it Impact Health?

Purpose is what guides our decisions, shapes our goals, defines our path, affects our choices, and helps us establish our life’s meaning. What each individual person’s purpose is, depends in part, on whether he or she tends to be more intrinsically or extrinsically motivated. Those who lean more toward being intrinsically motivated derive pleasure and/or purpose from helping others, while those who tend to be extrinsically motivated are driven more by tangibles (such as a hands-on project).

Purpose is what guides our decisions, shapes our goals, defines our path, affects our choices, and helps us establish our life’s meaning. What each individual person’s purpose is, depends in part, on whether he or she tends to be more intrinsically or extrinsically motivated. Those who lean more toward being intrinsically motivated derive pleasure and/or purpose from helping others, while those who tend to be extrinsically motivated are driven more by tangibles (such as a hands-on project).

However, while people may have a predilection for being intrinsically or extrinsically motivated, an individual who tends to be extrinsically motivated is able to look within him or herself and ultimately choose a purpose that helps others – should he or she wish to do so – and still derive health benefits from it. Only purposes that help others appear to positively affect health.

Dementia/Alzheimer’s Disease: Dementia occurs when brain cells (neurons) are damaged and no longer work properly. The type of dementia is characterized by the nature and location of the cell damage. The most common form of dementia is Alzheimer’s disease.

In “New Movement in Neuroscience: A Purpose-Driven Life,” published in the May-June 2015 issue of Cerebrum, co-authors Kaplin and Laura Anzaldi explain that “among the neurons most affected in Alzheimer’s, are those found in the hippocampus region of the brain (associated with short-term memory). Proteins called beta-amyloid and tau accumulate in neurons and lead to cell death and improper functioning. The damage in Alzheimer’s primarily manifests itself in memory loss.”

Until fairly recently, the only real advice given as to ways to potentially combat the development of Alzheimer’s has been to eat healthy, exercise, and keep your brain stimulated. But now, thanks to work by Patricia Boyle and colleagues at the Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center, there is reason to believe PIL could help reduce the risk of developing Alzheimer’s.

The study itself looked at more than 900 seniors with the same burden of plaques in their brain over a six-year time period. What researchers found is that those with a low PIL were 2.4-times more likely to progress to Alzheimer’s than those with a high PIL.

According to Kaplin and Anzaldi’s paper, that study, among others done by Boyle’s group, “suggest that PIL may have a protective effect on what is known as cognitive reserve and that people with a greater reserve can withstand more brain injury before developing neurologic symptoms.”

Risk of Stroke: The fifth leading cause of death in the United States, strokes occur when blood vessels fail to provide blood to oxygenate brain tissue. Strokes can run the gamut from brief, reversible transient ischemic attacks (TIAs), to massive, deadly attacks.

In 2013, scientist Dr. Eric S. Kim and his colleagues published a study that looked at PIL in relation to stroke in older adults. He and his team followed almost 7,000 participants, who had never had a stroke, over a four-year time period. They found that as the subjects’ PIL scores improved, the risk of stroke went down by as much as 22 percent.

Risk of Heart Attack: Turning to the leading cause of death in the United States, Kim and his team followed 1,500 subjects with cardiovascular disease for two years. What they found was that a higher baseline PIL was linked to a lower risk of heart attack. In fact, each unit increase of that baseline PIL on a six-point scale was associated with a 27-percent decreased risk of heart attack within two years.

What about Autoimmune Diseases (Such as MS) that Affect the Central Nervous System? Can PIL Play a Part in That, as Well?

To answer that, we must first differentiate between acute stress and chronic stress and their unique impacts on the body. Acute stress occurs over a short period of time, helping to initiate the body’s “fight or flight” response in the presence of something potentially harmful. Chronic stress occurs over a longer period of time.

When you experience stress, your brain releases a hormone into the bloodstream which further stimulates your adrenal glands to release the stress hormone known as cortisol. Cortisol has many positive benefits or tasks. For starters, it stimulates your body to metabolize molecules that increase energy production in your cells so your body can better handle the stressful situation.

When you experience stress, your brain releases a hormone into the bloodstream which further stimulates your adrenal glands to release the stress hormone known as cortisol. Cortisol has many positive benefits or tasks. For starters, it stimulates your body to metabolize molecules that increase energy production in your cells so your body can better handle the stressful situation.

Cortisol also has an effect on the immune system. When released into your bloodstream, it stimulates your immune cells to produce anti-inflammatory cytokines and inhibits your immune cells from producing pro-inflammatory cytokines. Or, in other words, the cortisol helps to temporarily block the body’s inflammatory response so it can better function during the stressful situation.

During chronic stress (that which is more sustained due to stressors such as a difficult job or home situation), cortisol levels remain higher than normal for prolonged periods of time. When this happens for any hormone in the body, the body can desensitize to that hormone. In regards to the immune system, the regulation of the inflammatory response will be thrown off, thereby increasing inflammation in the body. It can also have a negative effect on your immune system’s ability to respond appropriately when it is needed, or even not needed.

Inappropriate immune system activity, Kaplin and Anzaldi’s article points out, is thought to be a contributing factor in many central nervous system conditions including Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and multiple sclerosis.

How PIL Specifically Affects the Body

“Studies have shown that having a high purpose in life lowers resting cortisol,” says Kaplin. “Even if the participants were stressed, they were more likely to get their cortisol lower if they had a high PIL.”

Kaplin went on to explain that it’s when cortisol rises and stays high that the body’s immune system stops responding, thus having an effect similar to driving a car with the emergency brake on, so that in an emergency it no longer provides any assistance.

One example of PIL and a link to positive, objective changes in inflammatory response is interleukin 6 (IL-6), a cytokine that is important in the pro-inflammatory response of the immune system to a myriad of general stimuli, including bacterial and viral exposure. Since the dysregulation of IL-6 has been implicated in multiple central nervous system diseases, an experiment was conducted and published in Health Psychology in 2007 that looked at the blood levels of IL-6 and its receptor in a population of women. According to Kaplin and Anzaldi’s article, researchers found that higher PIL scores were associated with lower levels of the IL-6 receptor, implying less IL-6-mediated inflammatory activity. The relationship held when researchers controlled for sociodemographic and health factors, suggesting that PIL may be associated with a chronic calming effect on the immune system activity.

A study done by N. Rohleder in 2014 examined the impact on the inflammatory stress response. Higher levels of IL-6 were detected in the bloodstream of participants with low PIL scores in each subsequent stressful exposure.

Another study, this one from 2013, looked more generally at stress-related “transcriptomes” (a collection of all of the genes that are expressed in a specific system). Researchers wanted to explore which genes were active in immune cells in people with hedonic or eudaimonic wellbeing.

Hedonic wellbeing is based on the notion that increased pleasure and decreased pain leads to happiness. Eudaimonic wellbeing is based on the concept that people feel happy if they experience purpose and growth from challenges.

The study showed that the immune cells in people with hedonic wellbeing expressed more pro-inflammatory genes than did those with eudaimonic wellbeing. The correlation, according to Kaplin and Anzaldi’s article, therefore seems to imply that seeking purpose helps avoid a pro-inflammatory state, providing helpful information in the fight against neurological diseases such as multiple sclerosis.

“I think the inflammatory system is key here,” Kaplin says. “People with a higher PIL are less stressed because their purpose helps ground them, and when they are less stressed, they tend to handle neurological disease better.”

Stress, Kaplin is quick to point out, isn’t necessarily bad in and of itself. Everyone has it at some point. But how it’s interpreted can make the difference between its positive and negative effects.

Impossible to Ignore

In light of the positive research surrounding PIL, many doctors have turned to it as a matter of course in treating their patients. Do you remember that 20-question scale Crumbaugh and Maholick created in 1964 to assess PIL? That scale is still used today by many in the medical community, including Kaplin.

In light of the positive research surrounding PIL, many doctors have turned to it as a matter of course in treating their patients. Do you remember that 20-question scale Crumbaugh and Maholick created in 1964 to assess PIL? That scale is still used today by many in the medical community, including Kaplin.

“It gives me an important idea of whether the patient has a high or low PIL – both because of the implications of this score for overall health outcome long-term, but also because it alerts me to the fact that I may need to focus on PIL if the individual has none,” Kaplin says. “Conversely, if a patient has a high PIL despite experiencing depression, for example, I know where to focus my efforts and that the patient will likely do well if I can help to remove the impediment of his or her mood disorder.”

Getting from A to B (Finding Your PIL)

Aside from the studies with PIL, intuitively, it makes sense that having a purpose keeps us looking forward instead of backward. But finding that purpose, and sometimes having to adapt that purpose to reflect changes in physical ability, isn’t always an easy task and multiple factors can come into play, according to Amy Sullivan, PsyD, ABPP, clinical health psychologist at the Mellen Center for MS Treatment at the Cleveland Clinic.

Aside from the studies with PIL, intuitively, it makes sense that having a purpose keeps us looking forward instead of backward. But finding that purpose, and sometimes having to adapt that purpose to reflect changes in physical ability, isn’t always an easy task and multiple factors can come into play, according to Amy Sullivan, PsyD, ABPP, clinical health psychologist at the Mellen Center for MS Treatment at the Cleveland Clinic.

“We must understand that everyone’s life is driven by a multitude of things: responsibilities of work, caring for family members, et cetera,” says Sullivan. “That’s why, when looking for purpose, it’s important to look at the larger picture.”

To that end, when helping patients find purpose, Sullivan first seeks to help them understand what brings them joy and holds their interest, or more importantly, the things they feel passionate about and the things that give meaning to their life. She encourages them to process those things with a family member who truly knows them. Meditation and journaling can also help lead to finding one’s purpose.

It’s important to note here that being happy and having a purpose in life do not always go hand in hand. While happiness can have its positive impact on the body in terms of less stress, one’s happiness is often rooted in the moment. Meaningfulness, on the other hand, is more enduring and, as Frankl believed, can be the key component in helping a person survive great stress and suffering, as it did for him.

It’s important to note here that being happy and having a purpose in life do not always go hand in hand. While happiness can have its positive impact on the body in terms of less stress, one’s happiness is often rooted in the moment. Meaningfulness, on the other hand, is more enduring and, as Frankl believed, can be the key component in helping a person survive great stress and suffering, as it did for him.

One thing Kaplin suggests to his patients who are looking for their PIL, is to think back on crucible moments in life, i.e., those moments that were extremely challenging. How did you overcome it? What did you do? It is in those actions that he believes many people will find their true PIL.

In the writing, “Finding Power and Purpose in Your Crucible Moment,” by Warwick Fairfax, the importance of a crucible moment is explained. “I have found that when you use a crucible moment to help others, it can be very healing. When we take the focus off ourselves and try to use what we have been through to help others, it can make a huge difference in our spirit and our lives. Living such a life – using the pain of a crucible experience to help others – is what leading a life of significance is all about.”

Still unsure of your true PIL? Then consider looking back on goals you had when you were younger, or look to the stories of others to see if they resonate. Read inspirational books, or attend lectures. Stories that inspire make us dig deeper, Kaplin says. “We learn by example.”

However, of greatest importance in the search for one’s PIL, is that it’s your own, Kaplin cautions. “It has to be your belief, what you find rewarding in order for it to instill mental and physical health.”

For patients in Sullivan’s care, what brings joy and excitement to one’s life becomes obvious over time. And when they find their PIL, a decrease in depression is notable in both objective and subjective ways, she says.

“When working with MS patients to help them to find their PIL, I look at where they are in life,” Sullivan says. “For those who are newly diagnosed or in a new phase or change of function, it’s important for patients to have some space to grieve, and then to help them adapt to what comes next.”

For some, knowing their PIL isn’t the problem. Rather, it’s finding a way to pursue it within the framework of their physical abilities. The key is being open to tweaks and adjustments as they can often bring about PILs that are every bit as rewarding as the original version, something Kaplin has witnessed firsthand with patients.

“I had one patient who wanted to coach his child’s softball team but didn’t think he could, given his condition. I said, ‘Why not? Go show them that when you get knocked down, you get back up.’ And he did. And he ended up teaching the kids on that team about life as much as he did softball.”

Another patient had spent years dreaming about the traveling she wanted to do upon retirement. But, when the time came, her condition made it so she didn’t think she could still travel. Eventually, over time and with encouragement, she found destinations that could accommodate her desire to travel. Now, she maintains a travel log for people with disabilities. “A lot of times, you have to give something up to find your purpose,” Kaplin says. “Old goals can be changed and adapted to where you are now.”

PILs and Care Partners

One thing both Kaplin and Sullivan are quick to say, is that having a Purpose in Life is important for care partners as well. Whether caring for someone out of choice or necessity, care partners are in a unique situation, one where, very often, their own needs – physical and mental – are secondary to that of the person they are caring for. As a result, Kaplin says, rates of depression in care partners tend to be high, making them prime for diseases, too.

One thing both Kaplin and Sullivan are quick to say, is that having a Purpose in Life is important for care partners as well. Whether caring for someone out of choice or necessity, care partners are in a unique situation, one where, very often, their own needs – physical and mental – are secondary to that of the person they are caring for. As a result, Kaplin says, rates of depression in care partners tend to be high, making them prime for diseases, too.

While noble in many ways, it is important for these care partners to realize that they can better manage the impact of stress on their own bodies by taking care of themselves and finding their own PIL.

“It’s like that announcement on an airplane when they tell you that if the cabin suddenly loses pressure during the flight and the oxygen masks come down, you should put it on yourself first before helping a child,” Sullivan says. “You have to breathe so you can help your child in that situation. The same holds true for care partners and the person they’re caring for, as well.”

PILs are Different for Everyone…

As Kaplin suggests above, looking to the stories of others can inspire and often help you to step back, dig deep, and maybe even help lead you to finding your own PIL.

For Gary Heimbach, of Broken Arrow, Oklahoma, who was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in 1999, finding his purpose in life was a game-changer. “Before I was diagnosed, I was a workaholic climbing the corporate ladder,” Heimbach says.

“But with my diagnosis, I realized that my life purpose is not just about me, but more my relationship with my family, friends, and others. It made me realign and focus my priorities in life.”

Heimbach has come to embrace the notion that we “exist, live, or survive not to be takers but to give. Givers of time, values, and of our love.”

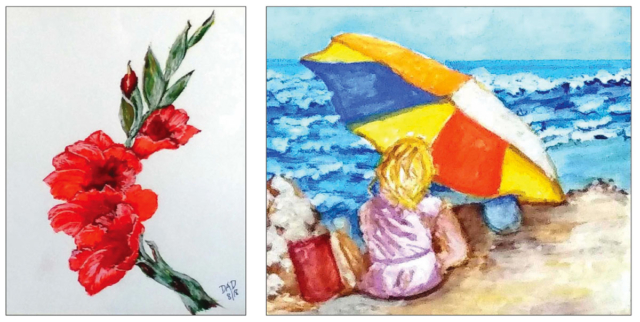

David Desjardins of Union, Maine – an MSAA Art Showcase participant – points to his determination to stay active and vital as his purpose in life. For him, the ways in which he accomplishes that goal have become more limited as his life progresses, but the determination to find a way remains.

“I think it’s human nature when faced with accepting loss and changes to one’s life to want to retreat and sit in a corner mourning that loss,” Desjardins says. “The challenge we all have is to overcome those feelings and find something on which to focus that gives satisfaction and draws attention away from the problems we are facing.”

Painting is one way he does that. “For me, painting regularly helps keep me feeling positive on many levels: when I first get an idea for a painting, I am looking forward to starting it and trying out my ideas; then when the painting is underway – and hopefully going well – I feel very positive and pleased; and when the painting is finished, a feeling of satisfaction and accomplishment takes over.”

For Maureen Whetstone of Hummelstown, Pennsylvania, her purpose in life had always been her role as a mother. But that purpose took on a new facet when, after first her daughter and then her son were diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, Whetstone ended up being diagnosed as well. “My diagnosis gave me clarity into what they were dealing with and feeling about their diagnoses. I saw how they were just going on with life, not letting it change their activities or steal their happiness. Their determination drives me to be stronger and braver and to set an example. Always.”

As part of that example, Whetstone continued working as a para professional at a nearby school district in the area of special education for many years. But as can be the case for someone living with MS, time to make a change for health reasons came. She took advantage of the pandemic to reassess her physical health in conjunction with her job and decided a change was needed. Now, she watches her youngest granddaughter every day. She says she still has purpose to wake up and get dressed every day. She misses her school life and helping the students who were in her care, but she’s at peace with her new job and treasures her new motivation to keep moving.

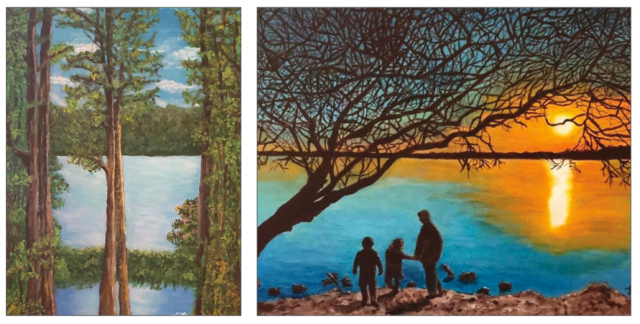

Kim Standard, of Douglasville, Georgia, another MSAA Art Showcase participant, found her purpose to be family – having and raising children – and maintaining a positive perspective for herself and others.

“I was raised with an aunt who was bedridden over thirty years with rheumatoid arthritis. Therefore, I saw a power chair as freedom to get around.”

Along the way, Standard started a blog. She saw it as a way to both work from home and get her message out regarding thankfulness, even in the face of adversity. She says she isn’t a writer but enjoyed the interaction between bloggers early on. Today, she spends some of her time painting – a skill she first tried in high school – only to revisit nearly 40 years later via an art class at her local senior center.

It’s Still Early, but…

According to Kaplin and Anzaldi’s article, “While research has suggested significant relationships between PIL and positive health outcomes, we cannot yet make any sweeping declarations about PIL being responsible for these actions. This is primarily because PIL studies that prove causation are difficult to design.”

But, they go on to write, “Identifying a Purpose in Life can have profound implications in overall life satisfaction and health, as it motivates and drives us even in the face of difficulties and hardships.”