Cover Story: Seeking Balance in MS

By Susan Wells Courtney and Tom Garry

Reviewed by Barry A. Hendin, MD

Do you ever feel dizzy? If so, please know that you are not alone. Many others – both with and without MS – experience this uncomfortable sensation.

Between 15% to 35% of the general population experiences dizziness at some point in their lives. This percentage increases to roughly half (49% to 59%) of individuals with MS reporting dizziness. In the United States, an estimated 7.5 million people seek medical attention for dizziness each year, making it one of the most common complaints seen by doctors and emergency departments.1

Dizziness can present in varying degrees and types, including vertigo, which is the sensation of spinning or movement around you. Naturally, dizziness and vertigo greatly affect balance and mobility. In addition, these types of challenges not only add to fatigue – a common symptom experienced by more than 70% of the MS population – but are also worsened by fatigue. Given these facts, it should come as no surprise that balance disorders are seen in 75% to 82% of people with MS who have mild to moderate disability.

In this issue’s cover story, we examine both dizziness and vertigo, as well as balance and mobility, in two separate sections. As you will see, the physical or psychological issues behind one’s dizziness can vary greatly, and once the exact cause is determined, effective treatments are available.

Part I: Dizziness and Vertigo

Initial Exam, Types, and Pathologies

As noted in the introduction, dizziness is a very common symptom among both individuals with MS as well as members of the general population. However, the type of dizziness someone experiences (vertigo is one type of dizziness), as well as the cause of that dizziness, varies greatly between different people. In order to identify the type of dizziness and its cause, the workup may include the following:

- Positional testing to see how the dizziness changes between different positions and also to observe eye movements when the head is turned certain ways

- A detailed history that includes duration of the dizziness and if it is continuous or episodic

- Discussion of possible triggers

- A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan when the central nervous system (CNS) is involved

- Additional testing, as needed

Once the specific cause is determined, a treatment plan may be implemented. Members of the MS community should keep in mind that when experiencing dizziness, just because someone has MS, does not necessarily mean that the dizziness is a result of disease activity. While a new lesion, inflammation, or an exacerbation may cause dizziness, at the same time, a different, non-MS-related issue may be to blame.

Dizziness is divided into four types:

- Vertigo (the sensation of spinning or your surroundings moving around you; it can be accompanied by nausea, vomiting, and hearing loss)

- Disequilibrium without vertigo (the sensation of falling)

- Presyncope (feeling close to fainting)

- Psychophysiological dizziness (light-headedness resulting from anxiety or panic)

Vertigo is divided into two main categories:

- Dysfunction or disease within the central nervous system, originating from pathology in the cerebellum or brain stem

- Dysfunction or disease within the peripheral nervous system, originating from the inner ear or vestibular nerve

Diagnosis

The first step in diagnosis is to determine the type of dizziness someone is experiencing. The next step is to distinguish between dysfunction within the central nervous system (relating to the cerebellum or brain stem) and the peripheral nervous system (involving the inner ear or vestibular nerve).

Identifying which nervous system is involved in the dizziness or vertigo is critical for the appropriate treatment of one’s specific cause of dizziness and vertigo. The “HINTS” examinations, which stands for Head Impulse (for maintaining fixation), Nystagmus (fast and involuntary eye movement), and Test of Skew (measuring uneven or oblique eye movement), is a quick, bedside method to distinguish between these two types of pathology.2

The HINTS examinations are performed by one’s doctor and consist of different exercises: fixating eyes on the doctor’s nose while the patient’s head is turned, looking side-to-side, and having one eye covered while fixating on the doctor’s nose. The resulting eye movements (maintaining or not maintaining fixation, slow versus fast nystagmus in different directions, and downward versus upward eye movement during fixation with one eye covered) indicate if the dizziness and vertigo are of central or peripheral origin, as well as which side is affected in vestibular neuritis.

In addition to learning what type of dizziness one is experiencing (vertigo, disequilibrium, or presyncope) and performing the HINTS examinations, the duration of vertigo and its trigger(s) are also important for an accurate diagnosis. The physician must also ask about the presence of headaches, tinnitus (ringing in the ears), hearing loss, and other neurologic deficits, to better identify the cause.

Some individuals experience chronic dizziness, which can result from different causes, particularly if an accurate diagnosis has not been made (often despite one or more doctor visits) and an appropriate treatment plan has not been implemented. In addition, some may also experience what is called “visual vertigo,” where “visually busy” surroundings can cause their symptoms to worsen. Examples of “visually busy” surroundings include large stores with rows of shelves, bright or moving lights, and traffic.

Central Nervous System Pathology

Vertigo that is caused by dysfunction within the central nervous system, relating to the cerebellum or brain stem, could indicate one of the following conditions:

- Stroke

- Tumor

- Hemorrhage

- Multiple sclerosis

When the central nervous system is involved, other neurological symptoms are often present, such as weakness, sensory changes, or confusion. For individuals with MS, vertigo and any concurrent increase in symptoms can be signs of inflammation from MS and possibly signs of a relapse. When a problem within the central nervous system is suspected, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan is performed.

Peripheral Nervous System Pathology

Peripheral pathology refers to disorders of the peripheral nervous system, involving the inner ear or vestibular nerve, and are frequently associated with vertigo, but are often benign and easier to treat.

These include:

- Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV)

- Vestibular neuritis

- Vestibular migraine (VM)

- Ménière’s disease (MD)

- Cervical vertigo

Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is the most common cause of “positional vertigo,” which is when someone changes position – possibly lying back or sitting up – and experiences vertigo. It is also the most successfully treated type of vertigo. BBPV may also cause nausea, visual issues, and nystagmus.

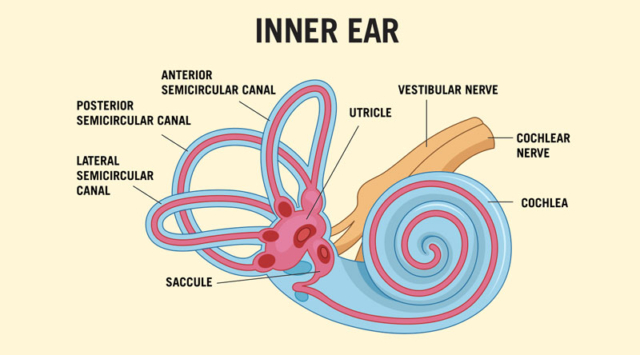

The mechanisms behind BPPV are well-defined. Otoconia, also known as “ear stones,” are small calcium crystals found in two organs of your vestibular system called the saccule (sensitive to vertical acceleration) and the utricle (sensitive to horizontal acceleration); both are located in the inner ear. Hairlike cells within these organs are stimulated by the otoconia to tell the brain that the body is accelerating, which is a vital component to balance.3

Other important components to balance include three semicircular canals found in the inner ear region of both ears, and each is paired with the corresponding one on the opposite side. These canals are lined with cilia (microscopic hairs) and filled with a liquid substance, signaling the brain as to which direction the head is tilting. The three canals are anterior (detecting forward and back “nodding of head” movement), posterior (detecting a tilt-like head movement), and lateral (for side-to-side head movement).3

Through different positional testing, such as the “Dix-Hallpike” and “Roll” tests, doctors may determine which ear canal has been affected, and on which side, according to the movement of the eyes during these tests. Vertigo triggers and duration differ slightly between these canals as well. BPPV occurs when otoconia is dislodged from the utricle and enters one of the ear canals.

Age, head trauma, inner ear disease, vestibular neuronitis, osteoporosis, and inner ear surgery, are among the causes of otoconia becoming dislodged.2 With BBPV, when the head is moved, these misplaced calcium crystals improperly stimulate the cilia within the affected canal, sending false movement signals to the brain that are not in agreement with those signals from the corresponding canal, causing the individual to have the spinning sensation known as vertigo.

BPPV can be treated through different maneuvers performed by a doctor, while the patient is in lying and sitting positions, and having their head turned in certain directions. Examples of these maneuvers to reposition the calcium crystals include the “Epley maneuver,” the “Barbecue maneuver,” and the “Semont maneuver,” depending on which canal is affected.

According to an article on a holistic approach to dizziness, the authors note that treatments may be used for more severe symptoms of BBPV. They explain that antihistamines and anticholinergic drugs may be used to relieve nausea, vomiting, and vertigo during the acute phase of BBPV. Examples of these medications include dimenhydrinate, diphenhydramine, and metoclopramide. However, vestibular suppressants, which are medications used to suppress nystagmus (abnormal eye movement) and reduce motion sickness, cannot be used during treatment with one of the maneuvers mentioned previously; nor can these types of medicines be used for a prolonged period of time without the risk of developing chronic dizziness.2

Vestibular Neuritis

Vestibular neuritis is a disorder causing the vestibulocochlear nerve, which is located in the inner ear, to become inflamed. Thought to be caused by a viral infection, this affects balance and can cause dizziness and vertigo. Treatments for vestibular neuritis include medications such as antivirals and those used to treat nausea, dizziness, and inflammation. Physical therapy with specific exercises can also help reduce the symptoms.4

Vestibular Migraine

Vestibular migraine (VM) is a neurological condition and is the second most common cause of vertigo. Symptoms include sudden attacks of vertigo, along with migraine symptoms that are experienced with at least half of these attacks. Vestibular migraine symptoms include: headache; sensitivity to light, sound, and/or touch; nausea and vomiting; and migraine aura.

Treatments can include lifestyle changes to reduce stress and fatigue, watching for dietary sensitivities, and rehabilitation exercises to help with balance issues. Medications may be given to help prevent vestibular migraine, such as tricyclic antidepressants, calcium channel blockers, antiseizure medication, and beta-blockers. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), motion-sickness medications, and antipsychotic medication may be used to help reduce the symptoms.5

Ménière’s Disease (MD)

Ménière’s disease (MD) is a rare disorder of the inner ear, affecting balance as well as hearing, and causing other symptoms such as vertigo and tinnitus (ringing in the ears). When someone is diagnosed with Ménière’s disease (MD), symptoms may come and go with this condition.6

MD cannot be cured, but treatments are available to help with symptoms. Treatments include vertigo medications and vestibular rehabilitation (exercises to help with balance). In more severe cases, middle-ear injections or surgery may be considered.7

Cervical Vertigo

Cervical vertigo is a condition where dizziness or vertigo (often more of a “floating sensation” versus spinning) is associated with neck pain. It may result from an injury to the neck, often occurring months or years earlier, or it may result from inflammation or arthritis within the cervical spine (neck) area. In addition to neck pain, dizziness, and a “floating” type of vertigo, symptoms can include balance problems and headache. Visual symptoms, such as rapid eye move-ment and visual fatigue, can also occur.

Cervical vertigo is treated by first addressing the problem causing neck pain, which might involve medications, physical therapy, and vestibular rehabilitation. Medications may include those that reduce inflammation and reduce dizziness, as well as muscle relaxants and pain relievers.8

Psychophysiological Dizziness

Looking at psychophysiological dizziness, differentiating between neurologic manifestations versus a psychogenic origin can be complicated. In other words, determining which is the cause and which is the effect can be confounding. While anxiety and depression are strongly associated with dizziness, the unpleasant sensations of dizziness and vertigo, along with the fear of falling and injury, can create a great deal of anxiety. Additionally, this type of dizziness may be provoked by external influences, such as being in a crowd, driving, or feeling confined.

Psychophysiological dizziness tends to last for months or longer, and may have periodic flare-ups and possibly presyncope (feeling close to fainting) resulting from hyperventilation. However, anxiety and depression frequently occur in combination with Ménière’s disease and Vestibular migraine (VM) as well, so determining the origin of dizziness and vertigo that are accompanied by anxiety and depression requires specialized and ongoing evaluation and treatment.

Antidepressants and anxiolytic medications may be given to help reduce the lightheadedness or vertigo associated with psychophysiological dizziness. Cognitive behavioral modification techniques with desensitization for situational anxiety may also be of benefit.9

Medication Side Effects

Another cause of dizziness that should not be overlooked is the use of certain medications. Frequently prescribed in older people or individuals with certain medical conditions, common medications that can cause dizziness include antiarrhythmics, antiepileptics, narcotics, muscle relaxants, and antiparkinsonian agents.2 If a certain medication is suspected to be causing dizziness or vertigo, one’s physician may be able to make adjustments to a prescribed medication.

Closing Notes

According to MSAA Chief Medical Officer Dr. Barry Hendin, “The symptoms of dizziness and vertigo are experienced by a large portion of not only the MS community, but the general population as well. As this article illustrates, these symptoms may be caused by any number of disorders – some serious, some benign and easy to treat.

“I would like to emphasize that new onset dizziness, vertigo, and imbalance, may indicate a relapse in someone with MS, but other causes are possible. When symptoms are new and persistent, prolonged, or severe, this warrants an evaluation by a clinician. In most instances, while concerning to the person experiencing these symptoms, such episodes do not pose any danger to the individual, other than the need to take the necessary precautions to reduce the risk of falling.”

Part II: Balance

Keeping Your Balance –

Literally – with MS

Remember the old adage, “It’s not what you say, it’s what you do”? That’s not entirely true when it comes to balance issues and – particularly – falls in people with MS, says Michelle H. Cameron, MD, PT, MCR.

“The most important thing you can do is to tell your provider if you’re falling or fearful of falling,” says Dr. Cameron, a neurologist and physical therapist. She explains that “saying something” is a prerequisite to “doing something” in terms of working with your clinician to develop an individualized plan to enhance balance and reduce the risk of falls.

Too often, she says, “People don’t tell us about falling because they don’t think there is anything that can be done. While we may not get to zero falls, we usually can reduce the number of falls, the severity of falls, and their consequences. As with so many of the challenges posed by MS, we as clinicians do not have a magic wand that can make the problem go away, but there are many steps we can take, and we can make it a lot better.”

Providers’ ability to manage balance problems stems in part from how frequently they see them. Dr. Cameron explains that 50% to 80% of people with MS have balance and gait dysfunction.10 She adds that about half of people with MS fall at least once in a three-to-six-month period, with 30% falling more than once in that interval.11

While the prevalence of balance problems in MS is well documented, Mandy Rohrig, DPT, MSCS, says that the profound impact of those challenges is not always fully appreciated, even by the people experiencing them. “Balance affects so many aspects of life for a person with MS, from obvious things like mobility, exercise, and risk of falling, to issues that may be less apparent but that are very important, such as self-image, socialization, and relationships with loved ones,” says Dr. Rohrig, a physical therapist, Multiple Sclerosis Certified Specialist, and member of MSAA’s Healthcare Advisory Council.

Indeed, a study of 75 people with MS who were ambulatory and who had a recent fall or near fall found that greater confidence in one’s balance was associated with both greater social satisfaction and greater social engagement.12 By contrast, Dr. Rohrig says, reduced confidence about balance can mean reduced social interaction. “If a couple is not going out because one of them is worried about falling, their world gets smaller and smaller, and it can negatively affect not only their relationships with other people, but also with one another.”

The Importance of an Individualized Approach

Dr. Rohrig explains that obtaining a thorough history is the first step in developing a plan tailored to a person’s specific balance challenges and needs.

“I partner with the person with MS and the care partner – if that person is involved and with my patient’s permission – to explore the circumstances when they have experienced imbalance, are concerned about falling, or had a fall. We do this investigative detective work together. This essential conversation helps to guide me in terms of how to best conduct the physical examination and overall assessment, and to then provide recommendations for interventions to improve balance and reduce fall risk. The interventions must address what is meaningful to the person,” says Dr. Rohrig, who has more than 14 years of experience practicing in a rehabilitation organization’s MS and vestibular/balance rehabilitation programs.

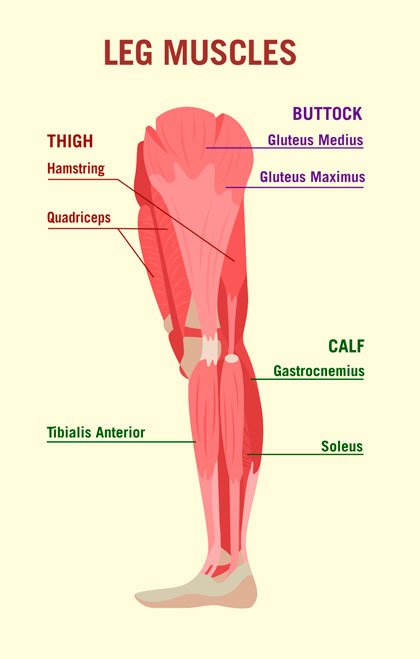

Her evaluation, she explains, includes looking at functional movements, such as sitting, standing, and walking, and assessment of strength, range of motion, spasticity, vision, and vestibular function. In terms of strength, a focus on the legs and core is particularly important, says Dr. Rohrig, who serves as Senior Programs Consultant for Can Do MS (at cando-ms.org), a national non-profit organization that delivers health and wellness education programs to people with MS and their families.

Once the evaluation is completed, Dr. Rohrig shares her recommendations with the person. “I spend a lot of time educating people about how balance works and then personalizing that information to their unique situation. Education facilitates a deeper understanding of the ‘why,’ which makes my recommendations – the ‘how’ – more meaningful to them.” (See “The Basics of Balance” sidebar) Dr. Rohrig says those recommendations typically cover three categories: exercise, environment, and, as indicated, use of adaptive devices.

Exercises generally focus on enhancing strength, range of motion, balance, and vestibular function, and often involve practicing going from sitting to standing and – in a safe corner – shifting one’s weight forward and backward and from side to side. The key, Dr. Rohrig adds, is for a professional to identify which exercises are appropriate for a person’s physical condition and functional needs. “I don’t want people using valuable energy and time on exercises that are not addressing a meaningful function for them,” she explains.

Environmental considerations include attention to maintaining balance on different types of interior and exterior surfaces, negotiating ramps and stairs, and maintaining balance in dynamic situations, such as a sidewalk crowded with people hurrying past.

Within a house, she adds, particular vigilance is needed in the kitchen and the bathroom, the two rooms in the home where people tend to be most active and face the most hazards, such as stepping into and out of a shower or tub, or moving from one workstation to another during meal preparation. She notes that the kitchen and bathroom also can be the hottest rooms in a home, whether due to a pot steaming on the stovetop or the warm mists generated by a long shower, which can be problematic for people with the heat sensitivity frequently seen in MS.

With respect to adaptive devices, Dr. Rohrig says that practical, individualized strategies can help people with MS maintain balance and reduce fall risk. She cites wearing firm-soled shoes and equipping bathrooms with bath chairs, tub benches, grab bars, and raised toilet seats or commodes.

Falls: Recognizing the Risk Factors

Much of what we know about the risk for falls comes from studies of older people in the general population and so is not necessarily applicable to people with MS, says Dr. Cameron. This neurologist has worked to remedy that shortcoming over the course of her career by conducting extensive research into fall risk and risk reduction specifically in the context of multiple sclerosis.

She explains that her research and that of other investigators has shown that among people with MS, the risk for falls tends to be greater:

- In secondary-progressive multiple sclerosis (SPMS) relative to relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS)

- With increasing age

- At transition points, such as when people move from RRMS to SPMS or first begin using an adaptive walking device

Dr. Cameron, a Professor in the Department of Neurology at Oregon Health & Science University, adds that the risk for falling also increases with the number of medications a person is taking.

The nature as well as the number of medications taken has an impact on fall risk she says. “Centrally acting medications, those that affect the brain, can negatively affect balance. Unfortunately, this includes many medications used to treat symptoms of MS such as spasticity and bladder control,” Dr. Cameron notes. For this reason, she adds, it is important for people with MS and their providers to carefully consider the need for each medication prescribed and to weigh the benefits and potential risks involved in its use.

One bright spot regarding medications and falls: In a study involving 248 ambulatory adults with MS, Dr. Cameron and her colleagues found that use of a disease-modifying therapy (DMT) was associated with a 48% decrease in fall risk.12 Dr. Cameron explains that this risk reduction was independent of people’s disease status or age, but she stresses that the study showed a correlation rather than establishing a cause-and-effect relationship between DMT use and fewer falls.

Putting Safety and Energy Conservation Ahead of Pride

In many cases, the risk of falling is increased not by factors beyond a person’s control, but by reluctance to take steps that would reduce that risk, such as by using an adaptive walking device or switching from high-heeled shoes to equally fashionable but safer flats.

Dr. Rohrig explains, “People with multiple sclerosis may hesitate to use mobility aids because it is felt that using these devices is ‘giving in’ to MS. I would encourage people to instead think of mobility aids as tools. The right mobility aid will allow you to do what you’re able to do more safely or allow you to do more!” She adds, “Use of mobility aids or wheeled mobility options are often considered an ‘all or none’ choice. In truth, it’s more a matter of what makes sense in a given time and place. Certain devices may be more appropriate in certain environments, circumstances, or time of day.”

Dr. Cameron agrees, saying, “Devices are there to help you to access the world, not to be seen as a sign of disability.” Too often, she adds, people initially are inclined to forgo activities that give them great enjoyment rather than making necessary adaptations. When she encounters such hesitance, this neurologist and physical therapist often employs motivational interviewing to identify a person’s goals and then help answer the question, “What steps can I take to keep doing what I want to do?”

Dr. Cameron adds that embracing the use of mobility aids or wheeled mobility options can significantly enhance quality of life. “One of my patients, a woman in her thirties, reluctantly began using a wheelchair. When I saw her shortly after that decision, she told me, ‘This is amazing. I wish I had done it sooner. I used to be exhausted at the end of the day. Now I have this nice, spiffy chair and I’m back to my life.’ She absolutely blossomed.”

Dr. Rohrig adds that the threats that balance problems pose to living a full life encompass not only falls but also the fear of falling. “Fear of falling can limit activity, and limited activity can contribute to deconditioning of muscles and balance. A person’s world can gradually become smaller as people begin to limit important activities,” Dr. Rohrig says. She adds that in addressing this fear, people may benefit from working with a mental health professional as well as with a neurologist and physical therapist.

Dr. Cameron agrees, noting that whether the issue is a fear of falling or actual falls, effective responses exist. By way of example, she cites research that she and her colleagues conducted with 78 people with MS who used walking aids but who were still experiencing falls. Half of the people were assigned to participate in six weekly one-on-one virtual sessions with a physical therapist. During those sessions, the therapist focused on ensuring that the person was using the right walking aid, that the aid was the right height for the person, and that the person was using the aid correctly. The other half of study participants served as a control group.

Compared to the control group, the people who worked with a physical therapist had a greater reduction in fall rate at the end of the six-week intervention and at six months. They also had an increased level of physical activity relative to the control group at six months.13 “The point is, there is a lot we can do to make things better, but it starts with a conversation about what you’re experiencing and what you’re concerned about,” Dr. Cameron says.

The Basics of Balance

When Mandy Rohrig, DPT, MSCS, outlines the basics of balance to her patients with MS, she starts by explaining that two primary systems are involved – the motor system and the sensory system.

“The motor system is responsible for providing sufficient strength and range of motion to the muscles involved with balance. It also plays a role in the sequency, timing, and coordination needed for those muscles to sustain upright, balanced posture. Key muscles include the calves (gastrocnemius/ soleus), lower leg (tibialis anterior), front and sides of thigh (quadriceps), back of thigh (hamstrings), buttocks (glutes), hip muscles, and abdominal muscles.”

Dr. Rohrig adds, “The sensory system involves our vision, vestibular (inner ear) system, and somatosensory input. Visual input – specifically, visual acuity – provides the nervous system with information about the environment, allowing us to anticipate or adjust to a situation. If vision is impacted by MS or other conditions, such as glaucoma, macular degeneration, or cataracts, balance can be impacted.”

She explains that the vestibular system of the inner ear interprets translational and rotational movements. “The inner ear has the critical role of communicating with the eye muscles through the vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR), which keeps vision steady as the body moves or the head turns. If this reflex is not functioning properly because of a lesion or other causes, a condition called nystagmus occurs. Nystagmus is often described by people with MS as a sensation of bouncing, shaking, or difficulty focusing, which obviously can be problematic when trying to safely maintain balance in a dynamic environment.”

Dr. Rohrig continues, “Somatosensory input is a fancy way of describing the sensory input from touch, pressure, and the joints – particularly the ankles, knees, and hips – about where the body is positioned in space. If a person with multiple sclerosis has numbness in the feet and has difficulty feeling the floor, the sensory input message from the feet to the brain is not as strong, which affects balance.”

Turning to how the two systems interact, Dr. Rohrig explains, “The body receives input from the sensory systems about its position and the environment and then communicates with the motor system about how to react to maintain safe movement and posture. The motor system in turn gives feedback to the sensory system about how to further optimize balance. The two systems and their components are at work all day every day to keep people balanced.”

While MS and its symptoms can detract from this efficient interaction, Dr. Rohrig notes that clinicians have many options for helping people meet the challenges involved.“Balance is complex” she says, adding, “but that complexity provides numerous opportunities to intervene.”

References

- García-Muñoz C, Cortés-Vega MD, Heredia-Rizo AM, et al. Effectiveness of Vestibular Training for Balance and Dizziness Rehabilitation in People with Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med. 2020 Feb 21;9(2):590.

- Koukoulithras I, Drousia G, Kolokotsios S, Plexousakis M, Stamouli A, Roussos C, Xanthi E. A Holistic Approach to a Dizzy Patient: A Practical Update. Cureus. 2022 Aug 4;14(8):e27681.

- Yetman D. What Are Ear Stones, Also Known as Otoconia? Published by Healthline. October 7, 2022. Accessed at https://www.healthline.com/health/ear-stones

- Vestibular Neuritis. Cleveland Clinic. Accessed August 2024 at https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/15227-vestibular-neuritis

- Vestibular Migraine. Cleveland Clinic. Accessed August 2024 at https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/25217-vestibular-migraine

- Ménière’s Disease. Cleveland Clinic. Accessed August 2024 at https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/15167-menieres-disease

- Ménière’s Disease. Mayo Clinic. Accessed August 2024 at

https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/menieres-disease/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20374916 - Cervical Vertigo. Cleveland Clinic. Accessed August 2024 at https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/23174-cervical-vertigo

- Lanska DJ. Psychophysiological dizziness. Published by MedLink Neurology. Updated 05.20.2024; originally released 10.22.2003. Accessed at https://www.medlink.com/articles/psychophysiological-dizziness

- Cameron MH, Nilsagard Y. Balance, gait, and falls in multiple sclerosis. Chapter 15. Handbook Clin Neurol. 2018;159:237-250.

- Cameron MH, Karstens L, Hoang P, Bourdette D, Lord S. Medications are associated with falls in people with multiple sclerosis: a prospective cohort study. Int J MS Care. 2015;17:207–214.

- Judd GI, Hildebrand AD, Goldman MD, Cameron MH. Relationship between balance confidence and social engagement in people with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2022 Jan:57:103440. Doi:10.1016/jmsard.2021.103440.

- Cameron MH, Hildebrand A, Hugos C, Woolscroft L. A walking aid selection, training, and education program (ADSTEP) to prevent falls in multiple sclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. Mult Scler J. 2024. DOI: 10.1177/13524585241265031.

Back