Dizziness and Vertigo

Do you ever feel dizzy? If so, please know that you are not alone. Many others – both with and without multiple sclerosis – experience this uncomfortable sensation.

Between 15% to 35% of the general population experiences dizziness at some point in their lives. This percentage increases to roughly half (49% to 59%) of individuals with multiple sclerosis reporting dizziness. In the United States, an estimated 7.5 million people seek medical attention for dizziness each year, making it one of the most common complaints seen by doctors and emergency departments.1

Dizziness can present in varying degrees and types, including vertigo, which is the sensation of spinning or movement around you. Naturally, dizziness and vertigo greatly affect balance and mobility. In addition, these types of challenges not only add to fatigue – a common symptom experienced by more than 70% of the MS population – but are also worsened by fatigue. Given these facts, it should come as no surprise that balance disorders are seen in 75% to 82% of people with MS who have mild to moderate disability.

Initial Exam

Dizziness is a very common symptom among both individuals with MS as well as members of the general population. However, the type of dizziness someone experiences (vertigo is one type of dizziness), as well as the cause of that dizziness, varies greatly between different people. In order to identify the type of dizziness and its cause, the workup may include the following:

- Positional testing to see how the dizziness changes between different positions and also to observe eye movements when the head is turned certain ways

- A detailed history that includes duration of the dizziness and if it is continuous or episodic

- Discussion of possible triggers

- A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan when the central nervous system (CNS) is involved

- Additional testing, as needed

Once the specific cause is determined, a treatment plan may be implemented. Members of the multiple sclerosis community should keep in mind that when experiencing dizziness, just because someone has MS, does not necessarily mean that the dizziness is a result of disease activity. While a new lesion, inflammation, or an exacerbation may cause dizziness, at the same time, a different, non-MS-related issue may be to blame.

Types of Dizziness

Dizziness is divided into four types:

- Vertigo (the sensation of spinning or your surroundings moving around you; it can be accompanied by nausea, vomiting, and hearing loss)

- Disequilibrium without vertigo (the sensation of falling)

- Presyncope (feeling close to fainting)

- Psychophysiological dizziness (light-headedness resulting from anxiety or panic)

Vertigo is divided into two main categories:

- Dysfunction or disease within the central nervous system, originating from pathology in the cerebellum or brain stem

- Dysfunction or disease within the peripheral nervous system, originating from the inner ear or vestibular nerve

Diagnosis

The first step in diagnosis is to determine the type of dizziness someone is experiencing. The next step is to distinguish between dysfunction within the central nervous system (relating to the cerebellum or brain stem) and the peripheral nervous system (involving the inner ear or vestibular nerve).

Identifying which nervous system is involved in the dizziness or vertigo is critical for the appropriate treatment of one’s specific cause of dizziness and vertigo. The “HINTS” examinations, which stands for Head Impulse (for maintaining fixation), Nystagmus (fast and involuntary eye movement), and Test of Skew (measuring uneven or oblique eye movement), is a quick, bedside method to distinguish between these two types of pathology.2

The HINTS examinations are performed by one’s doctor and consist of different exercises: fixating eyes on the doctor’s nose while the patient’s head is turned, looking side-to-side, and having one eye covered while fixating on the doctor’s nose. The resulting eye movements (maintaining or not maintaining fixation, slow versus fast nystagmus in different directions, and downward versus upward eye movement during fixation with one eye covered) indicate if the dizziness and vertigo are of central or peripheral origin, as well as which side is affected in vestibular neuritis.

In addition to learning what type of dizziness one is experiencing (vertigo, disequilibrium, or presyncope) and performing the HINTS examinations, the duration of vertigo and its trigger(s) are also important for an accurate diagnosis. The physician must also ask about the presence of headaches, tinnitus (ringing in the ears), hearing loss, and other neurologic deficits, to better identify the cause.

Some individuals experience chronic dizziness, which can result from different causes, particularly if an accurate diagnosis has not been made (often despite one or more doctor visits) and an appropriate treatment plan has not been implemented. In addition, some may also experience what is called “visual vertigo,” where “visually busy” surroundings can cause their symptoms to worsen. Examples of “visually busy” surroundings include large stores with rows of shelves, bright or moving lights, and traffic.

Central Nervous System Pathology

Vertigo that is caused by dysfunction within the central nervous system, relating to the cerebellum or brain stem, could indicate one of the following conditions:

- Stroke

- Tumor

- Hemorrhage

- Multiple sclerosis

When the central nervous system is involved, other neurological symptoms are often present, such as weakness, sensory changes, or confusion. For individuals with multiple sclerosis, vertigo and any concurrent increase in symptoms can be signs of inflammation from multiple sclerosis and possibly signs of a relapse. When a problem within the central nervous system is suspected, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan is performed.

Peripheral Nervous System Pathology

Peripheral pathology refers to disorders of the peripheral nervous system, involving the inner ear or vestibular nerve, and are frequently associated with vertigo, but are often benign and easier to treat.

These include:

- Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV)

- Vestibular neuritis

- Vestibular migraine (VM)

- Ménière’s disease (MD)

- Cervical vertigo

Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is the most common cause of “positional vertigo,” which is when someone changes position – possibly lying back or sitting up – and experiences vertigo. It is also the most successfully treated type of vertigo. BBPV may also cause nausea, visual issues, and nystagmus.

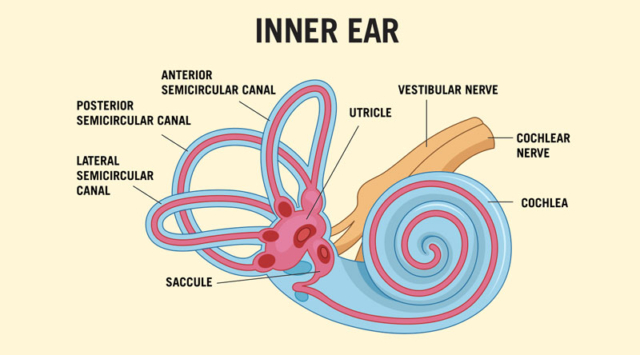

The mechanisms behind BPPV are well-defined. Otoconia, also known as “ear stones,” are small calcium crystals found in two organs of your vestibular system called the saccule (sensitive to vertical acceleration) and the utricle (sensitive to horizontal acceleration); both are located in the inner ear. Hairlike cells within these organs are stimulated by the otoconia to tell the brain that the body is accelerating, which is a vital component to balance.3

Other important components to balance include three semicircular canals found in the inner ear region of both ears, and each is paired with the corresponding one on the opposite side. These canals are lined with cilia (microscopic hairs) and filled with a liquid substance, signaling the brain as to which direction the head is tilting. The three canals are anterior (detecting forward and back “nodding of head” movement), posterior (detecting a tilt-like head movement), and lateral (for side-to-side head movement).3

Through different positional testing, such as the “Dix-Hallpike” and “Roll” tests, doctors may determine which ear canal has been affected, and on which side, according to the movement of the eyes during these tests. Vertigo triggers and duration differ slightly between these canals as well. BPPV occurs when otoconia is dislodged from the utricle and enters one of the ear canals.

Age, head trauma, inner ear disease, vestibular neuronitis, osteoporosis, and inner ear surgery, are among the causes of otoconia becoming dislodged.2 With BBPV, when the head is moved, these misplaced calcium crystals improperly stimulate the cilia within the affected canal, sending false movement signals to the brain that are not in agreement with those signals from the corresponding canal, causing the individual to have the spinning sensation known as vertigo.

BPPV can be treated through different maneuvers performed by a doctor, while the patient is in lying and sitting positions, and having their head turned in certain directions. Examples of these maneuvers to reposition the calcium crystals include the “Epley maneuver,” the “Barbecue maneuver,” and the “Semont maneuver,” depending on which canal is affected.

According to an article on a holistic approach to dizziness, the authors note that treatments may be used for more severe symptoms of BBPV. They explain that antihistamines and anticholinergic drugs may be used to relieve nausea, vomiting, and vertigo during the acute phase of BBPV. Examples of these medications include dimenhydrinate, diphenhydramine, and metoclopramide. However, vestibular suppressants, which are medications used to suppress nystagmus (abnormal eye movement) and reduce motion sickness, cannot be used during treatment with one of the maneuvers mentioned previously; nor can these types of medicines be used for a prolonged period of time without the risk of developing chronic dizziness.2

Vestibular Neuritis

Vestibular neuritis is a disorder causing the vestibulocochlear nerve, which is located in the inner ear, to become inflamed. Thought to be caused by a viral infection, this affects balance and can cause dizziness and vertigo. Treatments for vestibular neuritis include medications such as antivirals and those used to treat nausea, dizziness, and inflammation. Physical therapy with specific exercises can also help reduce the symptoms.4

Vestibular Migraine

Vestibular migraine (VM) is a neurological condition and is the second most common cause of vertigo. Symptoms include sudden attacks of vertigo, along with migraine symptoms that are experienced with at least half of these attacks. Vestibular migraine symptoms include: headache; sensitivity to light, sound, and/or touch; nausea and vomiting; and migraine aura.

Treatments can include lifestyle changes to reduce stress and fatigue, watching for dietary sensitivities, and rehabilitation exercises to help with balance issues. Medications may be given to help prevent vestibular migraine, such as tricyclic antidepressants, calcium channel blockers, antiseizure medication, and beta-blockers. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), motion-sickness medications, and antipsychotic medication may be used to help reduce the symptoms.5

Ménière’s Disease (MD)

Ménière’s disease (MD) is a rare disorder of the inner ear, affecting balance as well as hearing, and causing other symptoms such as vertigo and tinnitus (ringing in the ears). When someone is diagnosed with Ménière’s disease (MD), symptoms may come and go with this condition.6

MD cannot be cured, but treatments are available to help with symptoms. Treatments include vertigo medications and vestibular rehabilitation (exercises to help with balance). In more severe cases, middle-ear injections or surgery may be considered.7

Cervical Vertigo

Cervical vertigo is a condition where dizziness or vertigo (often more of a “floating sensation” versus spinning) is associated with neck pain. It may result from an injury to the neck, often occurring months or years earlier, or it may result from inflammation or arthritis within the cervical spine (neck) area. In addition to neck pain, dizziness, and a “floating” type of vertigo, symptoms can include balance problems and headache. Visual symptoms, such as rapid eye move-ment and visual fatigue, can also occur.

Cervical vertigo is treated by first addressing the problem causing neck pain, which might involve medications, physical therapy, and vestibular rehabilitation. Medications may include those that reduce inflammation and reduce dizziness, as well as muscle relaxants and pain relievers.8

Psychophysiological Dizziness

Looking at psychophysiological dizziness, differentiating between neurologic manifestations versus a psychogenic origin can be complicated. In other words, determining which is the cause and which is the effect can be confounding. While anxiety and depression are strongly associated with dizziness, the unpleasant sensations of dizziness and vertigo, along with the fear of falling and injury, can create a great deal of anxiety. Additionally, this type of dizziness may be provoked by external influences, such as being in a crowd, driving, or feeling confined.

Psychophysiological dizziness tends to last for months or longer, and may have periodic flare-ups and possibly presyncope (feeling close to fainting) resulting from hyperventilation. However, anxiety and depression frequently occur in combination with Ménière’s disease and Vestibular migraine (VM) as well, so determining the origin of dizziness and vertigo that are accompanied by anxiety and depression requires specialized and ongoing evaluation and treatment.

Antidepressants and anxiolytic medications may be given to help reduce the lightheadedness or vertigo associated with psychophysiological dizziness. Cognitive behavioral modification techniques with desensitization for situational anxiety may also be of benefit.9

Medication Side Effects

Another cause of dizziness that should not be overlooked is the use of certain medications. Frequently prescribed in older people or individuals with certain medical conditions, common medications that can cause dizziness include antiarrhythmics, antiepileptics, narcotics, muscle relaxants, and antiparkinsonian agents.2 If a certain medication is suspected to be causing dizziness or vertigo, one’s physician may be able to make adjustments to a prescribed medication.

Closing Notes

According to MSAA Chief Medical Officer Dr. Barry Hendin, “The symptoms of dizziness and vertigo are experienced by a large portion of not only the multiple sclerosis community, but the general population as well. These symptoms may be caused by any number of disorders – some serious, some benign and easy to treat.

“I would like to emphasize that new onset dizziness, vertigo, and imbalance, may indicate a relapse in someone with multiple sclerosis, but other causes are possible. When symptoms are new and persistent, prolonged, or severe, this warrants an evaluation by a clinician. In most instances, while concerning to the person experiencing these symptoms, such episodes do not pose any danger to the individual, other than the need to take the necessary precautions to reduce the risk of falling.”

References

- García-Muñoz C, Cortés-Vega MD, Heredia-Rizo AM, et al. Effectiveness of Vestibular Training for Balance and Dizziness Rehabilitation in People with Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med. 2020 Feb 21;9(2):590.

- Koukoulithras I, Drousia G, Kolokotsios S, Plexousakis M, Stamouli A, Roussos C, Xanthi E. A Holistic Approach to a Dizzy Patient: A Practical Update. Cureus. 2022 Aug 4;14(8):e27681.

- Yetman D. What Are Ear Stones, Also Known as Otoconia? Published by Healthline. October 7, 2022. Accessed at https://www.healthline.com/health/ear-stones

- Vestibular Neuritis. Cleveland Clinic. Accessed August 2024 at https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/15227-vestibular-neuritis

- Vestibular Migraine. Cleveland Clinic. Accessed August 2024 at https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/25217-vestibular-migraine

- Ménière’s Disease. Cleveland Clinic. Accessed August 2024 at https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/15167-menieres-disease

- Ménière’s Disease. Mayo Clinic. Accessed August 2024 at

https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/menieres-disease/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20374916 - Cervical Vertigo. Cleveland Clinic. Accessed August 2024 at https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/23174-cervical-vertigo

- Lanska DJ. Psychophysiological dizziness. Published by MedLink Neurology. Updated 05.20.2024; originally released 10.22.2003. Accessed at https://www.medlink.com/articles/psychophysiological-dizziness

Updated in October 2024 by Dr. Barry Hendin, MSAA Chief Medical Officer