The MS Process

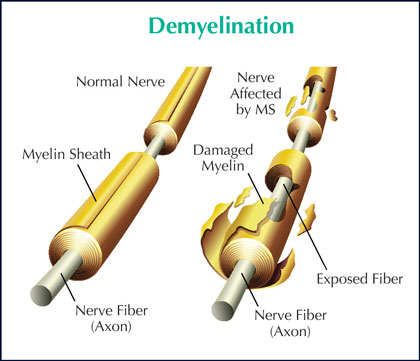

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a disease of the central nervous system (CNS). The CNS consists of the brain, optic nerves, and spinal cord. With MS, areas of the CNS become inflamed, damaging the protective covering (known as “myelin”) that surrounds and insulates the nerves (known as “axons”). In addition to the myelin, over time, the axons and nerve cells (neurons) within the CNS may also become damaged. MS is thought to be an autoimmune disease, where the body’s own white blood cells, known as lymphocytes, become misdirected and attack the body’s own myelin.

The damage to the protective covering and also to the nerves disrupts the smooth flow of nerve impulses. As a result, messages from the brain and spinal cord going to other parts of the body may be delayed and have trouble reaching their destination – causing the symptoms of MS. Each person with MS may experience different types and severity of symptoms – and some may experience only one or two symptoms, while others may experience a combination of symptoms.

The damage to the protective covering and also to the nerves disrupts the smooth flow of nerve impulses. As a result, messages from the brain and spinal cord going to other parts of the body may be delayed and have trouble reaching their destination – causing the symptoms of MS. Each person with MS may experience different types and severity of symptoms – and some may experience only one or two symptoms, while others may experience a combination of symptoms.

The symptoms of MS range from physical symptoms to emotional/psychological symptoms to “invisible” symptoms. Examples of physical symptoms include mobility issues, muscle stiffness, bladder problems, and tremor. Anxiety, cognitive changes, and depression are among the emotional/psychological symptoms seen with MS. And the so-called “invisible” symptoms refer to problems such as fatigue, numbness, pain, and visual disorders. Please see pages 16-17 for a full listing of common symptoms.

Areas of inflammation and damage in the CNS are known as “lesions.” The changes in size, number, and location of these lesions may determine the type and severity of symptoms. Disease activity may also be evaluated from these changes in the size or number of lesions. Frequently, MS may be “clinically silent,” showing no increase in symptoms, yet continuing to show signs of disease activity within the CNS, as seen on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) – an important evaluative tool.

For individuals with relapsing forms of MS, early and continued treatment with a disease-modifying therapy (DMT) can often slow the “clinically silent” disease activity in the brain, reducing the size and number of active lesions. This is one reason why most neurologists recommend beginning treatment as soon as possible after an MS diagnosis is established – not only for those with relapsing forms of MS, but often for those with progressive forms of MS as well.

For individuals with relapsing forms of MS, early and continued treatment with a disease-modifying therapy (DMT) can often slow the “clinically silent” disease activity in the brain, reducing the size and number of active lesions. This is one reason why most neurologists recommend beginning treatment as soon as possible after an MS diagnosis is established – not only for those with relapsing forms of MS, but often for those with progressive forms of MS as well.

Treatment is also typically recommended for individuals with clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), which is the first appearance of an MS-like symptom or event and a common precursor to more MS-like activity and a confirmed diagnosis. When someone has CIS, starting treatment at this potential first sign of MS can reduce the risk of being diagnosed with MS.

Anyone starting a DMT should note that these types of treatments cannot be effective unless taken exactly as prescribed and without missing doses, so adherence is critical. For more information on types of MS, please see pages 6-7. Details on disease-modifying therapies begin on page 13.

In addition to the lesions, areas of scar tissue may eventually form along the areas of permanently damaged myelin. These areas of scar tissue are referred to as “plaques.” The term “multiple sclerosis” originates from the discovery of these hardened plaques. “Multiple” refers to “many”; “sclerosis” refers to “scars.”

As noted earlier, lesions and plaques are viewed on a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanner. This technology is used to help diagnose MS and to evaluate disease progression at various intervals. The MRI and other tools are described in the section titled, “Diagnosing MS and Evaluating Disease Activity,” beginning on page 10 of this booklet.