Genealogy: A Rewarding Hobby With Easy Access

by Loretta Evans, AG

While author Loretta Evans, AG, researched her family’s history, she discovered this photo of her great-great grandmother Eliza Cusworth Staker, shown here with two of her daughters and a granddaughter. Shown also is the first photo that Loretta uncovered while learning about her family’s history. This is her Great Grand Aunt Cora Steward. After finding the photo, Loretta was hooked on genealogy.

Family history is one of the fastest growing hobbies in the United States. More and more people have discovered the fun of tracing their ancestors. With the advent of the internet, it has become easier than ever before.

Genealogy is a versatile hobby. One’s family history may be recorded with a simple pen and paper, or it can involve expensive computer equipment. People with MS are discovering that genealogy is fun and flexible enough to allow for when they are having both good and bad days.

I got started doing family history research back when I was in college. I had been reading my great grandmother’s obituary in a faded scrapbook. It said that she was survived by a brother and a sister. I realized that I had information on three of her brothers, but I had no record of a sister. Suddenly, I had to find that missing sister. I had found my great grandmother and her brothers in the 1860 census in a small town in Ohio. No sister was mentioned. I got the roll of microfilm for the same town in the 1870 census. At that time there was no index, so I started with the first family recorded by the census taker. After reviewing records of dozens and dozens of families, I finally found the right people. The ink had faded, but I could make out a six-year-old sister named Cora. Later I found a family photograph of a large lady in a big hat, labeled “Aunt Cora.” Finding Cora hooked me on genealogy.

Since my diagnosis with MS, I realized that genealogy was perfect for me. On days when I felt good, I could search the web, write letters, or visit a Family History Center. On days when fatigue took over, these people — now deceased — could wait until my energy returned.

Doing family history research is like a detective looking for a missing person. Working from known information and making educated guesses has led me to public records that have helped fill in the gaps in my pedigree.

People just getting started should begin with some blank forms. Pedigree charts show one person’s direct ancestors. Family group sheets record all the children in each family. There are several places on the internet where blank forms can be downloaded. One place is at Ancestry.com: www.ancestry.com/charts/ancchart.aspx.

Start with yourself. On a pedigree chart, record your birth date and place. If you are married, record the date and place of your marriage and birth information for your spouse. Then fill in what you know about your parents and grandparents. Most charts show four or five generations. Fill out what you know from memory, but use a pencil, so you can make corrections if necessary. When recording each woman, use her maiden name if you know it.

Then take one family group sheet. If you are married, create one sheet for you and your spouse. If you have children, record information about them on that same chart. Then fill out another family group sheet showing you as a child. This sheet will include your parents and brothers and sisters. Once again, do the best you can from memory.

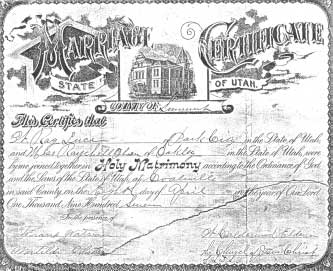

This dashing young man is Loretta’s grandfather, Willard Ray Luce, Sr. The marriage license is for his marriage to Rachel Olsen, Loretta’s grandmother. They were married in Summit County, Utah, on April 8, 1907.

If you are able, fill out a form for each set of grandparents, showing your parents as children with your aunts and uncles. By now you probably won’t know all the details.

At this point start contacting relatives. You can ask living people to give you dates and places. They may remember details about relatives who have died. Be sure to record who gave you what information.

Then look through documents you own. Do you have any official certificates of birth, marriage, or death? Has someone saved newspaper articles or funeral programs? A trip to a family cemetery may yield additional information.

About this time you may find that typing your information into a computer can help you keep track of all that data. There are a number of excellent programs available. I like the Personal Ancestral File 5.2. The biggest advantage is that it is free and can be downloaded from the internet. Go to www.familysearch.org. Click on “Order/Download Products.” Then click on “Software Downloads — Free.”

For each piece of information missing from your charts, think about what kind of records might contain the missing data. For example, a tombstone could give both birth and death dates. Some headstones even list the names of spouses or parents. The 1930 census could show everyone living with the family the day the census was taken. It will also show their relationship to the head of the household, each person’s age, the state or country where they and their parents were born, the occupations of each adult, and even whether the family owned a radio.

This photo is of the B. F. Larsen family, taken about 1922. Here Loretta’s grandparents pose on a porch with their three sons and daughter — who later became Loretta’s mother.

Many records have been posted on the internet. Some sites charge money for their services, but many are free. Be aware that not everything on the internet is accurate. If you record data you have found, be sure you record where you found it. If you discover two sources that conflict, you might be able to judge which is the most reliable.

The more you learn about your family, the more you will appreciate them. You will find heroes and black sheep, but most of all, you will find real people. Their struggles will help you appreciate your own. Many of us have various challenges we must face each day while living with MS. Despite these hardships, our ancestors had some challenging moments as well. For instance, you may become fatigued while food shopping, but you probably never had your crops destroyed by grasshoppers; and while travel might be challenging at times, you never put everything you owned into a covered wagon and walked two thousand miles to a new home you had to build yourself.

Delving into your family’s past often reveals many interesting facts that could surprise you. You may find that your youngest son looks a lot like your great grandfather. You may discover that an uncle loved to play the violin, just like you do. The more you find about your family, the more you will discover about yourself.

Ten Things You Can Do to Preserve Your Family History

Shown here is Loretta’s great-grandfather’s sister. Married twice, her full name was Emily Luse Fletcher Rogers.

- Write your own life story. You don’t necessarily need to start with your birth and go chronologically. Write about brief memories as they come to you. If you save your memoirs on a computer, you can put each short essay into chronological order at a later time, if you choose to do so. Be sure you save a backup of your computer file on disk or print out a paper copy. Computers have been known to crash at the most inconvenient times.

- Organize and label family photographs. How many people have boxes of snapshots in various places throughout the house? By labeling the pictures and organizing them, the collection will be far more valuable. Be careful to label photographs with a pencil or photo-quality marker. Ball-point pens can leave ridges on the right side of the picture. You may want to organize the pictures into albums. If you do, use acid free materials and label the people in each shot. You may know everyone in your album, but 100 years from now, will your descendants recognize anyone?

- Transcribe family letters, diaries, or other documents. If you have letters or journals that belonged to your ancestors, you might want to preserve them. One way is to copy them into a computer file, so more family members can enjoy them. Be sure not to “correct” spelling and punctuation. The way the items were originally spelled is part of the charm. The history of your family played a role in the history of the world. A local historical society or university library might also be interested in having a copy.

- Document family heirlooms. You may own items that belonged to your ancestors. Do any of your relatives know the stories behind the treasures? Take time to photograph each item and to write a brief story about who owned it and why it is important. You can make a file of these stories, either in a binder or on your computer. Keeping an extra copy in your safe-deposit box at the bank is a good idea in case of natural disasters. This file can help your relatives know what items you own are of significance to your family’s history.

- Document your descendants. Do you have birth, marriage, and death information for each of your descendants and their spouses? It wouldn’t hurt to have copies of official certificates on file as well. A computer genealogical program can help you organize this data, but paper forms also work well.

- Update your resume. A resume can be important when job hunting, but it can also be a good source of family history. Do you have a record of each job you have held? How about volunteer work you have done? Do you have a list of awards you have received? Taking time to record milestones as they happen is much easier than recalling them if you should need the information.

- Interview older family members. Each time someone dies, their memories are no longer available to the rest of us. If you have parents, grandparents, or other elderly relatives, now is a good time to record their memories. Make an appointment and give them some of the questions you would like to ask. You can record the interview with either a tape recorder or a video camera. Be sure that the microphone is close enough that the person’s voice is clearly recorded. Be aware of background noises that could interfere with the recording, such as a barking dog or a ticking clock. Usually about an hour is long enough. If you have more questions, plan a second visit. Be sure to give the person a copy of your interview. With his or her permission, you can distribute the tape to other family members. Local libraries and historical societies might like a copy as well.

- Collect data on your ancestors. Using a blank paper form or a computer genealogical program, record birth, marriage, and death dates and places for your ancestors as far back as you can remember. Then visit with other family members to see if they have additional information. Write down where you got the information. Did Aunt Mary tell you her birth date, or did you get it from Cousin Martha? Do you have any documents, such as certificates, funeral programs, or newspaper clippings? If so, record the information and the source.

- Visit a Family History Center. Family History Centers are found throughout the world. They are sponsored by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, but their services are free and open to the public. You do not need to be a member of that church to use the facilities. You can find the address and contact information for a center by going to www.familysearch.org/Eng/Library/FHC/frameset_fhc.asp and typing your location. Trained people will be there to help you get started.

- Take a class on genealogy. Local genealogical societies and Family History Centers often offer classes on genealogical research. In addition, there are several places on the internet that offer online classes. Some of the best beginning courses are “Finding Your Ancestors” (#FHGEN 68) and “Introduction to Family History Research” (#FHGEN 70). They are available through Brigham Young University, and they are free of charge.

The National Genealogical Society provides an excellent series of online classes. For more information, go to www.ngsgenealogy.org/.

About the Author

Loretta Evans of Idaho Falls, Idaho, is an Accredited GenealogistCM researcher specializing in Midwestern United States Research. She is a freelance writer and lecturer on genealogical topics. She has been reading microfilm, wandering cemeteries, and fostering a love/hate relationship with her computer for more than 30 years. When she is not doing genealogy, Loretta likes to cook, read, and work in her garden. She has a husband, five grown children, and a dog. They all love her despite her fascination with people who are no longer living.

Loretta contributed this two-part article for MSAA’s feature article in this issue of The Motivator. She also contributed a second article for a new column appearing on page 48 of this issue. Many thanks go to Loretta for her generosity.